Reading Highlights 2025

Theories of not quite everything

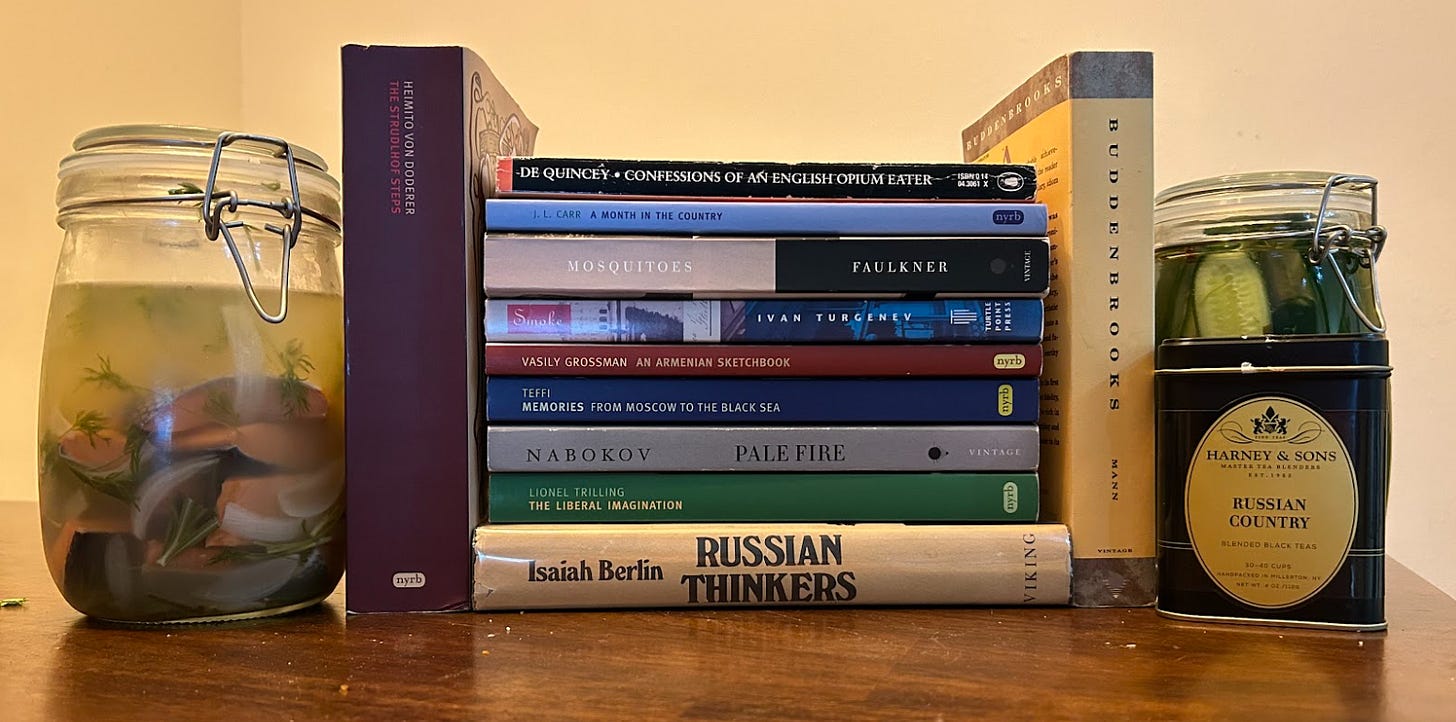

It was a long and eventful year for still being shy of the full 365 days. I was involved in four plays, was chased away from a military installation in Nevada, escaped a flash flood, languished on a 48-hour Amtrak ride from Kansas City to Los Angeles, drank scotch in a Taito City jazz bar and bourbon with a Shanghai bureaucrat in Iwamatocho, climbed a minor mountain in Wyoming (in the snow!) and ate “free”1 lobster tail in Maryland. I also got into pickling, largely through culinarily reading Turgenev’s Sketches from A Hunter’s Album.

I read a lot, but alas, I didn’t make good on many of the promises I made in Kyoto. My reading was more focused than usual: the average year of publication of all the books I read in 2025 (37, if you must know), is 1907, most of them translated from Russian or German. I suppose I’m honing in on the era and the subjects that truly interest me, but at the same time, I hope 2026 rejuvenates my desire to read more widely, not just in space, but in subject matter. Only generalists go to heaven.

The Father, August Strindberg, 1887.

Translated by Elizabeth Sprigge. Intense. It’s interesting to read intense plays after writing Passion’s End, and wondering what experiences the playwright is pulling from. This has a pretty dark and bleak view of romantic love. Also interesting to read a playwright from this era other than Chekhov — Strindberg and Chekhov are both downers, but Chekhov is considerably more humorous, which makes his tragedy that much more poignant. Strindberg’s unrelenting bleakness inoculates your sensitivity; Chekhov keeps you raw.

Buddenbrooks, Thomas Mann, 1901.

Translated by John Woods. Started this back in October 2024, and I’m glad I took my time with it — though the delay began to weigh heavy on my emotions after a while! A marvelous piece of writing: his descriptions of people and places and emotions are all so lush and lucid, a bit like literary deep focus: everything is presented in such crisp detail, I couldn’t plow through it; I needed to take breaks. Deep love for and frustration at all the main characters, but especially Tony and Thomas. So much to think about: the pressures of duty crushing their naturalness and costing them, possibly, their happiness. But all rendered so subtly: lucidity is a key complement to lushness. Never does Mann’s narrative overflow the levy of his cool, crisp style — no bursts of fevered, rampant introspection, a la Dostoevsky or Faulkner. But he is on a par with both. The description of Hanno’s death from typhus makes Turgenev’s depiction of Bazarov’s final illness, which Chekhov praised to the skies, look like a finger painting. Oh, what a tremendous, tremendous book. (There were some definite resonances, very prominent in places, with Flags in the Dust: family honor, the ledger of births and deaths, the ultimate survival of the womenfolk, etc. I wonder if Faulkner read the book, and if he would acknowledge the influence.)

Smoke, Ivan Turgenev, 1867.

Translated by Constance Garnet. Marvelous, with new heights for Turgenev’s capacity to describe complex introspection in a few words, a few carefully crafted metaphors. The social commentary is also extremely funny. Deeply sad, but it ends hopefully, for Litvinov, at least; Irina and Potugin. Sad. Gorgeous. Worth the wait. Late Turgenev is better, I find: Torrents of Spring is also from the same period, and features a similar, and similarly moving, arc of tragedy and redemption.

A Sentimental Journey, Laurence Sterne, 1768.

I bought this a while ago, possibly when I plundered the Santa Paula bookstore when it closed and everything was a bargain. Charmingly written, with something of the authorial presence of Flann O’Brien, though without the absurdist humor — though does Rabelaisian humor qualify as absurdist? Certainly not in the same way that Flann O’Brien does, at the very least. Want to read Tristram Shandy at some point, as a result of this: fun, funny, well-written, light satire.

Confessions of An English Opium-Eater, Thomas de Quincey, 1821.

An astounding book. The prose is magnificent, and the story remarkable: his dreams in particular are wild. I’m convinced the ones related to architecture influenced both Susanna Clarke in Piranesi and Christopher Nolan in Inception. Affecting, gorgeously written, and thought-provoking: a terrific whim-of-the-moment read.

An Armenian Sketchbook, Vasily Grossman, 1965.

Translated by Robert and Elizabeth Chandler. Beautiful stuff. His stream of consciousness between narrative and metaphorical commentary (his fixation on stones, his extended metaphors on hermits and sunsets and the beauty of women) has a delightful and disarming simplicity to it: he’s not a self-aware writer at all, or at least doesn’t come across that way. A welcome refresher to the hyper-introspection of a lot of the early 20th century, pre-war literature I love so much. I especially enjoyed the chapter in which he met the Catholicos and the old peasant man. His descriptions, though more dependent on metaphor, remind me of Turgenev’s: they have a simple and direct evocativeness. They’re not labored, heavy, or crafted: they seem effortless. By the end, I felt like I’d spent time in a distinct landscape and gotten to know its yearly cycle of pallor and blush.

Bread in the Wilderness, Thomas Merton, 1953.

My first full encounter with Merton. Beautiful and thought provoking — and oddly contemporary. Surprising in places to recall that it was written in the 1950s. A lot I need to chew on. The role of the Psalms in promoting purity of heart, the central concern — according to Merton, echoing St. John Cassian — of the monastic life.

A Month in The Country, J.L. Carr, 1978.

Brideshead Revisited meets Lilies of the Field, with a touch of B.J. Novak’s Vengeance. I shall say no more.

Mosquitoes, William Faulkner, 1927.

Early Faulkner is excellent, though this certainly lacked the restraint that surprised me in Flags in the Dust. Some of the prolonged scenes are astonishingly well-written — dramatic, cinematic, with some of his finest and wittiest dialogue. The conceit and its execution were both excellent, though it’s certainly a downer. About a group of affected bohemian-types in New Orleans who get stuck on a lake in a boat for a few days, during which bitter hilarity ensues.

Memories, Teffi, 1931.

Translated by Robert Chandler, Elizabeth Chandler, Anne Marie Jackson, and Irina Steinberg. The first finished of the (far too many) books I brought with me on my ill-starred roadtrip. Beautiful. Some highlights include Gooskin, the fried eggs business, the hair’s breadth escape from Odessa thanks to V, her eerie discussion of gemstones and her friend M, and the long stretch on the Shilka, with especially the haunting Holy Saturday night when she they hear the churchbells from the shore, and she remembers her little sister. A fascinating transitional period in Russian literature: as with Grossman in An Armenian Sketchbook and now in Stalingrad, events have obliterated the literary charm of mapping the subtleties of psychological topography, but the pre-Revolution tradition of stylistic depth and psychological penetration are still here — the old style has yet to exchange its traditional, psychologically rich subject matter for shallower, more propagandistic fare.

In Praise of Shadows, Junichiro Tanizaki, 1933.

Translated by Thomas J. Harper and Edward G. Seidensticker. Helped me resonate with the atmosphere and vibes not just of modern Japanese cinema, but of Bashō, Kenkō, and the older tradition. The beauty of shadows and relations rather than of things; the thingness of things muted, reduced to unobtrusive instruments to craft and highlight shadows. Plus, his reflections at the end voiced something I’d noticed about general Japanese mores in their films, about the isolation and exclusion of the elderly in industrialized Japanese society. That makes sense of Ozu’s oeuvre in particular.

Virgin Soil, Ivan Turgenev, 1877.

Translated by Constance Garnet. Not his best, but certainly better than the Penguin Classics note (“his later novels lack the balance and topicality of his earlier works”) implies. Certain sections felt rushed, and the dialogue between his lovers just never quite sticks the landing; but the defects are somehow compensated by the story, which is so different from his earlier fare. Marianna is an especially interesting, unusual character for Turgenev. Nezhdanov, meanwhile, reminds of Trofimov in The Cherry Orchard, but infused with the essence of Turgenev’s previous superfluous men. It’s a combination that doesn’t quite work: he could have done more with him. He hints at Nezhdanov’s complexity, but the hints don’t reveal the nature of that complexity so much as merely make its presence evident. Still, it worked more than A Nest of the Gentry. As always, I loved the side characters: Solomin, Paklin, Sipyagin, Kallomyetsev, Valentina Mihalovna. A melancholic conclusion to his oeuvre.

Russian Thinkers, Isaiah Berlin, 1978.

I finished this during the sleepless night before I left for Japan, but I’d been reading essays from this since I bought it on a trip to Solvang in February. A game-changer in terms of affecting my perspective, not just of Russian history but of life in general. A non-fiction highlight of the year, comparable in intellectual impact to Popper’s Open Society a few years back. Combined with Buddenbrooks, it inspired my two favorite essays. Berlin grounds the major figures of 19th century Russian literature in their wider European context — and does so without the Dostoevsky fetish that prejudices the enthusiasts for Russian literature in contemporary Catholic literary circles. Like Lionel Trilling (see below), Berlin offers a liberal, but deeply humane, assessment of Russia’s imperial writers. He’s also a marvelous stylist in his own right — and immensely well-read. Enriched my experience of Turgenev, Chekhov, Tolstoy, and Dostoevsky, and introduced me to Herzen and Belinsky.

The Adventures of Arsène Lupin, Gentleman-Thief, Maurice Leblanc, 1907.

Translated by Alexander Teixeira de Mattos. What delightful fluff! Lighthearted, funny, and very French. Arsène Lupin is France’s answer to Sherlock Holmes (who appears, under the preposterous pseudonym of Holmlock Shears, in one of the stories): he is an elegant cat burglar with a Robin Hood heart-of-gold streak and Jeeves-like omniscience. It’s odd, perhaps, that I should read the lion’s share of these tales of a late-19th century French cat burglar in my spare time on trains and “on break” while in Japan, and finished the book in Incheon Airport in Seoul during a 20-hour layover. But that’s our global age, isn’t it?

The Liberal Imagination, Lionel Trilling, 1950.

Picked this up in Lincoln, Nebraska, at the ICLE conference, where it immediately provided an intellectual refuge. A genuinely wise man, grounded in literature, sensitive to the world’s constants and the variables, and a marvelous stylist — a consolation devoutly to be wished. Trilling’s wisdom was certainly hard-won. Jacques Barzun, in an obituary for Trilling, with whom he worked at Columbia University for years, said of his friend that

in the I930s a young American who would be a critic faced, in life and art, the choice between a reactionist aestheticism upholding the autonomy of the work of art and the Marxist interpretation (and employment) of art as a weapon in the Class struggle. Like many others, Lionel was drawn to Marxism by his idealism and generous humanıty; but not tor long. He soon tound unacceptable the apparatus imposed on thought by Marxian teachings and even more repellent the deeds of the practition-ers. He began to develop his own Third Position, a position on the Left as a critic of the Left. Out of it came all the premises and conclusions in politics, art, morals, and psychology that made him from the outset unclassifiable. (A Jacques Barzun Reader, p. 134)

If I gush, it’s only because Trilling’s voice is a soft but welcome music amid the atonal white-noise of postmodern, increasingly postliberal life. He’s a true friend in history, in Mencius’s sense. Favorite essays: “Manners, Morals, and the Novel”; “Art and Fortune”; and “The Princess Casamassima”.

The Strudlhof Steps, Heimito Von Doderer, 1951.

Translated by Vincent Kling. An utterly magnificent book. Read from July to October — perfect to finish it in that time, given that it ends in the fall. So different from Buddenbrooks, but still deeply akin to it. Both have a crisp, restrained style, but Doderer’s authorial presence is stamped on every page — an utterly self-aware, vaguely self-reproaching commentator, not unlike Tolstoy’s authorial presence, and yet not quite like him, either. Tolstoy’s satirical contempt waxes during his depiction of society, but it yields to earnest truth-seeking elsewhere; Doderer maintains a cool, mocking detachment that somehow manages never to slip into actual cynicism. Both, too, are masters of metaphor — Doderer to outrageously extended degrees. In that sense, the book was also redolent of Gormenghast. Dear, dear Melzer. I had a harder time with Rene, but Melzer charmed me in the midst of all his emotionally stunted bumbling from woman to woman and job to job, and into something like wisdom. And the gradual, believable transformation of Thea Rokitzer from a self-absorbed ditz to a reserved but open-hearted woman is masterfully executed. As you plow through the very long, seemingly tedious fourth part, you suddenly realize that Doderer has snuck you onto the rollercoaster car of the rising action, which cranks slowly, with a kind of merry mechanical fulfillment, toward a richly eucatastrophic climax involving a severed leg and an invisible Cupid.2

Pale Fire, Vladimir Nabokov, 1962.

Started this spring, set aside for some reason, and then finished in Lander, Wyoming, on a hot October Saturday. Bizarre and beautiful. The offhand metaphors are stunning, but Nabokov is just too… I don’t know, you have to wonder whether or not he husbanded his genius to good purposes. Kinbote is perfidious. Returning to the book after the summer hiatus, I was struck by the realization that Kinbote might be modeled after Andre Gide, which helped make his vile character, if not palatable, at least a bit more intelligible. But I’ll admit, the ending left something to be desired: as with many a Gene Wolfe story, these kinds of unreliable narrator, ‘weird’ books are hard to conclude, simply because no conclusion can possibly match the weirdness attained in the narratives.

The Aeneid, Virgil, translated by Robert Fitzgerald.

A reread, as part of teaching high school English. I remember disliking it the first time through, but what credence should be given to the forceful opinions of callow youth? A lot, it turns out. What a deep disappointment — and I can’t even blame immaturity or reading it too fast, the usual pious excuses for not liking a Great Book when you read it at Thomas Aquinas College. All the most interesting human bits are rushed, and its vaunted “ambiguities” don’t strike me as deliberate acts of genius, but as failed executions. Bring up primary and secondary epic all you want, Virgil is a bad epic poet: Milton, much as I may dislike him personally, has a much superior grasp of pacing and dramatic structure, both of which are essential to epics of both kinds. And Dante? I’ve also been re-reading The Divine Comedy, and Dante is even better than Milton at building anticipation across cantos, at all the aspects of narrative and epic art that Virgil lacks. Virgil’s stature is as irritating as Hitchcock’s among contemporary cinephiles: his works paved the way for his betters, but they don’t hold up. It’s hard to tell what Virgil was getting at by the end, but it’s also hard to care — it’s one deus ex machina after another. None of the characters are all that interesting, Aeneas least of all: piety isn’t an epic virtue, and even if it was, Virgil’s gods aren’t worth the effort. Homer’s gods are richer and more mysterious; if they’re not more deserving of piety, it’s at least easier to understand a man being mystified at their sublimity. If Virgil hoped to write a Roman complement to Homer, he proved what every literate Roman already thought: imitations pale. One thing I will say in the poem’s favor, however: the theme in the earlier two thirds of the book of conquerors and conquered, of the inherent violence and lies of homeland rhetoric, immediately provided a lens, fascinating for its antiquity, through which to view contemporary ethno-national violence in Israel/Palestine and Russia/Ukraine. There is, indeed, nothing new under the sun. That Virgil seems to let this theme wither at the end is one more reason to dislike the poem: he might have said something profound, but settled on saying something pretty and politically useful.

Because TANSTAAFL!

I came across this Asymptote Blog post by the translator of the book, Vincent Kling, which astonished me for its blatant failure to comprehend the work of art in front of him. Certainly, the novel lacks a conventional plot, but it’s unthinkable to me that Doderer’s tremendous effort was all a deliberate attempt to undercut the novelistic conventions of his time, or to create a German idiom contemplable in and for itself. Yet in every description of the book, that’s about all you get about it — nothing at all about the emotional material in the book. Could it be that no one can countenance the possibility that Doderer, a former Nazi who renounced his faith in National Socialism midway through the war, and who loathed himself for his earlier blindness to Hitler’s depravity, might be in any way a sympathetic human being? The book’s afterword reinforces this same interpretation — it shows neither mercy nor compassion to Doderer, but instead approves his own self-loathing. The book is an indisputable masterpiece, but it’s rhetorically and psychologically safer to emphasize it as a masterpiece of eccentricity, which distances the reader from any emotional participation in the interior life of a man who made an egregious error in judgment — an error he admitted, recanted, and regretted for the rest of his life. The emotional commingling with Doderer through the emotional commingling with his characters — who are not simply stock characters, whatever Kling may say — is rich and enriching, perhaps even more so because it involves associating with someone so much wiser in the wake of a great mistake. The secular literary gurus, for all their celebrations of the transgressive and the authentic, once again prove themselves the chairman’s new puritans.

You read so much more appreciatively and deeply than I do! Buddenbrooks being an example where you got much out of it versus my impatient race to finish it. Great, thoughtful round-up post.